Consider the famous Italian adage “traduttore, traditore”—literally, translator, traitor. Maybe this untranslatability angst is one of the things that best defines the work of the translator. More often than not, translators are worried about failure, about things getting lost in translation.

A corollary to the saying above is that the true measure of a translation is its degree of invisibility: it is good as long as it is not perceived. The translated narrative must be as perfectly readable and enjoyable as if that were the original language. If the reader notices something is wrong in the text, she will most likely blame the translator rather than the author.

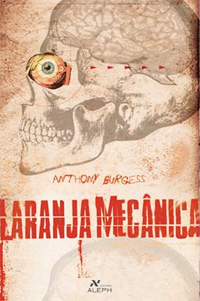

In 2003, I was invited by a Brazilian publishing house to do a new translation of Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange. This classic novel had already been translated to Brazilian Portuguese in the early 1970s, and it was a prime quality job, done by an award-winning translator, Nelson Dantas. But, after thirty years, even the finest translations can become outdated. They are still good and readable, but they lose their edge, their élan, their vitality.

In A Clockwork Orange‘s case, the earlier translation was fruit of the zeitgeist of the seventies: the slang was different then, the phrasal constructions and the kind of neologisms of one’s choice. (Agglutinations were all the rage then—portmanteau words sound wonderful in Portuguese.) Now, however, a second reading of that translation proved a weird experience to me—weird in a bad way.

While reading the original remains an strong, powerful experience because the cognitive estrangement, to use Darko Suvin’s expression, is all there, we still find that near-future, ultraviolent, russified Britain strange. We are compelled to believe it anyway, the imagery of those words being much too strong for us to do otherwise, but reading the translation just didn’t make me feel the same. I got entangled in a jungle of old words, words seldom used anymore (the agglutinations now doesn’t seem so fresh and catchy as before), and I simply couldn’t immerse myself in the story any longer. The estrangement was gone.

Burgess wrote A Clockwork Orange after, among many other things, a visit to the USSR, where he witnessed the most weird thing: gang fights in the streets, something he thought was more commonplace in the UK. He filtered that through his experience and created his world. When we translate a story, we strive to recreate said story (or to transcreate it, a concept proposed by late Brazilian poet and semioticist Haroldo de Campos, a notion that I find very elegant), give some of us and our culture to receive something in exchange for it.

This is not the same thing as proposing we act as tradittori and change the text as we wish, not at all: the trick (if trick it is) is to do a little thing of what Jorge Luis Borges taught in his wonderful short story “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote“, about the behavior of the man who dared to rewrite Don Quixote in the early 20th Century, word by word: “Know Spanish well, recover the Catholic faith, fight against the Moors or the Turk, forget the history of Europe between the years 1602 and 1918, be Miguel de Cervantes.”

For the nine months that the task of translating that novel took me, I followed the Menard method. I tried to be Anthony Burgess. And, more important than that, I tried to act as if Burgess was born in Brazil and had decided to write A Clockwork Orange in Portuguese. Because that’s what it is in the end: every translation is in itself a piece of Alternate History. Every translated novel is the novel that it could have been if its original writer had been born in the country of the translator.

As Nelson Dantas had done before me (and, no question about that, as another Brazilian translator will do after me in the future), I translated A Clockwork Orange to the best of my abilities. And, in the process, I wrote another book: the possible Clockwork Orange. For a translator of a novel will always write another novel, and yet it is the same—it is a novel its original author would be able to recognize. A story found in translation, never lost.

Fabio Fernandes is a writer and translator living in São Paulo, Brazil. He translated for the Brazilian Portuguese approximately 70 novels of several genres, among them A Clockwork Orange, Neuromancer, Snow Crash, and The Man in the High Castle. He is currently translating Cory Doctorow’s Little Brother and the Vertigo/DC Comics series Hellblazer.